Why do we need a biennial? I have often asked myself this question. I have been to many places with major international cultural events, i.e., before COVID-19, that was. During Lockdown, I co-organized an artist-in-residence program to think about what the implications, threats, and opportunities of COVID-19 are for cultural practitioners. Everything turned out quite differently than we had hoped, the great upheaval failed to materialize, and in a time marked by crises many are now simply trying to return to the status quo. Have we really used the trillions of Euros and Dollars so thoughtlessly and without reflection, only to maintain a system that urgently needs a change?

The concept of biennials or major cultural events was already discredited before COVID-19. They are dominated by the art market and influencer posing. An international chic and hipster community, old intellectual hardliners, head-shaking know-it-alls, and naive do-gooders met there to applaud a powerless self-promotion of artist-curators and gallerist-egos. Many seriously want to show that the world should become better, but with what example do they go ahead?

Kochi-Muziris Biennale

I was at the Kochi Biennale for the first time in 2016, and I already thought that something different was being done here—better—with the heart in the right place and a vision that was oriented towards making a concrete, real difference. There were children’s art camps, public events where anyone could and did come, school children and their mothers came from the villages of Kerala, run-down barracks, warehouses, docks were opened so that art students from all parts of India could exhibit there, international artists were invited to see the locations before they conceived their side-specific installations. There were a large number of art educators, many projects were focused on ecology, social impact, critique of the ruling class. Little children, who use their school vacations to look at art, laughingly ask foreigners on the street where they come from, only to ask even more joyfully with great pride and enchanting charm if they like Kerala.

Fort Kochi is a melting pot of India, where spiritual, colonial, indigenous, national, political, cultural influences have converged for centuries. Kochi is an architectural jewel covered with Che Guevara graffiti and communist election posters. Goats and cows walk among the rickshaws, and everything smells of Kerala’s spice garden. Fresh fish is sold on the beach, while container ships and military reconnaissance vessels pass in the background. It is a vibrant city.

The fifth edition 2022/23

The 2022 Biennale started with organizational chaos. This is not really surprising in India, but it does show the challenges that Covid left behind. Many buildings stood empty for four years, or were just used for storage, which further reduced the already fragile building technology infrastructure. An incendiary letter on e-flux from participating artists attests to the frustration. Organizing a major international event in India may not be an easy task in itself, but doing so after two years of pandemic is actually impossible. It is all the more surprising that after two weeks of catastrophically communicated delays, the miracle of the Kochi Biennale happened again. Some things are still under construction even three weeks after the official partial opening. But most of it is professionally installed—in warehouses and barracks. The power of many artworks shines through the chaos.

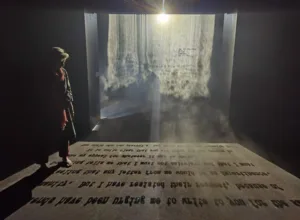

Some large video installations, such as commissioned work by CAMP’s „Bombay Tilts Down (2021-2022)“ from Mumbai at Aspinwall or Amar Kanwar’s „Such a Morning (2017-19)“ from Delhi at Anand Warehouse, have transformative power. CAMP uses CCTV Surveillance footage and mixes it with percussive chants about solidarity, oppression and hope in Mumbai’s poorest neighborhoods.

In contrast, Kanwar’s work is poetically quiet, a journey into darkness. A mathematics professor, perhaps going blind, prepares for the darkness. What a task for a visual artist – a preparation for a life without sight! This is not only about the existential questions of survival, but about the limits of art, how far does art reach beyond perception? The video installation is extended by an installation of miniprojectors, in which elements of the film are selected and captured in settings. Lined up next to each other, the film thus becomes a linear copresence that allows the visitor to walk around between the images. The visitor is in a place of reverberation, of memory, the images of the film are faded, transformed, surreal.

A general trend is also intensifying here. More and more artists are using the medium of film. Projections and screens are everywhere. Magically disturbing is the installation of Jitish Kallat „Covering Letter“ (2012), the work has been seen many times before, but in the south of India it unfolds a completely different power. Ghandi sent a letter to Hitler on July 23, 1939. It was addressed ‚Dear friend‘. Ghandi emphasized that Hitler was the only person who could prevent the brutality of this war. The letter is projected continuously by Jitish Kallat on a cloud of mist. A touch of history is felt.

Since we are dealing with time media, it is impossible to cope with all of this, and so there is a competition of screens and projection sizes. There are many works on political, ethnic and social conflicts to be seen. Every story would be worth to be retold here. But the narrative medium reaches its limits here. The visitor needs time, but she is rewarded with a variety of perspectives from the point of view of the oppressed. In the age of portable pocket screens, it is appropriate to rely on this medium because our viewing habits are changing, the static image and text without dramaturgical staging are lost in the battle for attention.

It is nice to see that the curator shows great diversity in hanging. Large rooms with picture areas completely without text panels are beneficial – these hang in the hallway of the administrative wing of Aspinwall. The biennial gives the works space, the walls never seem crowded. This invites one to linger.

Art for the mind

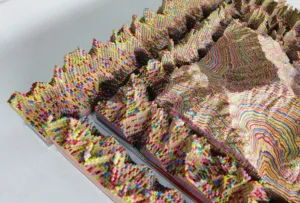

Yohei Imamura „tsurugi“ (2022) is a highlight in technical mastery. Over two years, Imamura used a silkscreen technique to create a 3D model of a mountain by layering. A video explains the process. The reflective layers are almost as varied as the more than 1000 layers of paint that create the 3D model of the mountain. It starts with the topographic maps, which are themselves a layer of abstraction from reality. I think of Baudriallard’s simulacrum, of postmodern concepts of mapping. Imamura traces each elevation plane in order to transfer it individually to a silkscreen plane. This meditative tracing is also a preparation for mountain climbing; knowledge of the terrain is essential for survival.

By reproducing the mountains in 3D through layering, we are reminded of geological processes. It would be interesting to know what are the geological stratifications of the mountain itself, is there any correlation? Probably not. The whole could be created on a 3D printer, but here the inner design principles would be radically different, algorithmic, vector-based, tech-scanned. Criticism of a wide variety of technical media is clearly implied here. And so we find ourselves confronted with an object that combines different levels of representation and abstraction, created through an innovative form of masterful screen printing. Technical reproduction, imagination, construction, the intertwining of space and plane, of creativity and precision meet here.

A radical increase of the conceptual can be found in the works of Iman Issa „Lexicon (2012-19)“ questions the relation of language, image, and imagination. The starting point are art-historical descriptions of images that are not shown. Instead, from these textual descriptions, Issa isolates formal elements that can be seen as sculptures next to the descriptions. It is an intellectual game that seems a bit out of place. However, this kind of textual, Western, critical, perhaps based on postcolonialist discourse does not really resonate.

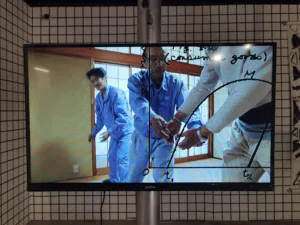

Biennale of the people

This Biennale of the people has a different accent: political, participatory, inviting. This becomes very clear and evident in the works of Marcos Avila-Ferero „Theory of the wild gees, notes on the workers gestures (2019)“. Avila-Ferero asked retired Japanese workers to repeat their movements of the work processes in their professional life. We see workers moving air in human chains. The whole thing seems so absurd and senseless, so exposing and inhuman, that the whole exploitation of labor becomes immediately tangible. The technical tracing of the physical motion sequences illustrates how the rationalization of labor uses the human body as a tool. We see how, after decades of routine, the body adapts and deforms to the work processes. Over the duration of the exhibition, dancers will be invited to respond to these work processes. This is exciting to imagine.

The curatorial statement reads, „even the most solitary of journeys is not one of isolation, but drinks deeply from that common wellspring of collective knowledge and ideas.“ Nowhere is this more evident than in the works of the Student Biennial. You can feel the verve of young artists, the poetry that unfolds in the warehouses from the colonial era. The works of young artists „drink deeply from that common wellspring of collective knowledge and ideas,“ – they take a big gulp.

This again is not unusual, in fact not that remarkable, because art students all over the world do this. Except in Kochi they are represented at the Biennale, they are visible to an international audience, they are heard, their voice is amplified and sounds in a chorus, they are not alone, they represent a whole generation, the generation to which the future belongs and which is taken away from them by the egoism of the ideals of old white men.

The work of Nilofar Shaikh of VNSGU „Healing Map, Bench“ is such an example. A bench, with murals in the background, invites the viewer to confront the issue of violations and to enter into dialogue with the environment.

Dheeraj Jadhav shares his way of seeing with his installation „Planting Conversation“, which is strong and compelling.

Nabam Hem, Taba Yaniya and Ejum Riba invite us into the world of the Tani clan with their large installation „Tani Nyia Nyji Muj“. It is moving and thought-provoking.

The community art project Bhumi has worked in lockdown with a community in Bangladesh. Local materials and traditions result in a round of figures that exemplify the heart of this biennial. It can be seen on the sidelines of the biennial at the TKM Warehouse.

I always try to spend a few days at a biennial, I find it important to interact with the environment. In Kochi, I drink my chai on the boardwalk and laugh heartily with the people from Kerala, even though we don’t have a common linguistic language. The south of India is incredibly hospitable, warm, carried by a spirituality that perceives life in every counterpart. These encounters are the real energy of the Kochi Biennale, without them none of this would be possible here. And I am beginning to understand what it means to truly live differently. It is the nature and the culture, the people and the spirituality, the harmony of the world that can be heard here. It is a radical counter design to the over saturated affluent societies. In the curatorial statement we find: „The human need to think freely without proscription, in spite of, and sometimes because of repression, all point to the way we react to conflict. The only enemy is apathy. That has no name or face, and it lies entwined with its bedfellow-self-censorship.“

It is the Biennale of the people.

[Best_Wordpress_Gallery id=“19″ gal_title=“Kochi“]

Further reading: