Art Before Theory (short summary)

Christoph Kluetsch

This lecture is the final one in my winter series. I have given six lectures so far, and I have been challenging myself throughout. Today, I am taking on my biggest challenge yet. I have been exploring topics that interest me—topics that represent a collision between Western art history, Indian spirituality, and postmodern thinking. I find this intersection to be a fascinating space to operate in. In my previous lectures, I have examined temple architecture, problems of representation, and stylistic comparisons between seemingly unrelated artistic traditions. Today, I will delve into the most challenging topic for me: the idea of art before theory.

This lecture will be somewhat experimental. I will attempt to go before theory while still using theoretical concepts to explore this idea. My perspective on art shifted dramatically after leaving the Western Hemisphere. When I first traveled to India and later to China, I realized that the timeline I had been operating on—along with the concepts I had been learning and teaching—did not align with reality.

To start, I want to discuss a controversial artifact: the Makapansgat Pebble, found in South Africa. This small pebble, only five centimeters in size, was likely transported approximately 50–60 kilometers from its original location around three million years ago. This suggests that it was intentionally moved. At that time, the beings responsible for this action were not what we would call humans. They were conscious beings of some kind, existing long before any conventional human timeline.

What is intriguing about this stone is that it resembles a human face. Archaeologists have studied it and found that some of its markings were intentionally made. The question is: is this an artifact or simply a found object with human-like qualities? This raises a deeper question—what comes first: art or the capacity to perceive something as art? Do we suddenly decide to create art out of an empty space, or must we first be in a certain disposition to recognize something as art? If, three million years ago, there were beings who perceived and valued aesthetics, then the artistic impulse might be inherent in consciousness itself.

A common narrative suggests that prehistoric art was purely utilitarian—used for ritual, worship, or survival rather than for aesthetic appreciation. I would like to challenge this idea. The Western historical perspective often assumes a linear progression of human intellectual and artistic development, from primitive beginnings to increasing complexity. I disagree. The discovery of artifacts from 30,000–40,000 years ago, such as the Chauvet Cave paintings in France, reveals an astonishing level of artistic sophistication. Pablo Picasso, upon seeing the Lascaux cave paintings (dated to 17,000 years ago), famously remarked, „We have learned nothing.“ He saw no evidence of artistic progress—only continuity.

Filmmaker Werner Herzog explored this idea in his documentary The Cave of Forgotten Dreams, which examines the Chauvet Cave paintings. These paintings are nearly twice as old as those in Lascaux and exhibit an equally high level of skill and artistic expression. Herzog proposes that the human mind, with its ability for aesthetic perception, appeared all at once, rather than developing gradually. This challenges the assumption that consciousness and creativity emerged through a slow evolutionary process.

Traditional historical narratives depict human development in neat, linear timelines—first one stage, then another, leading to progressive improvement. However, these models are based on ideological assumptions about progress. They align with capitalist notions of advancement, which frame history as a constant process of moving forward. This perspective influences how we view art history as well. Alfred Barr’s famous diagram of 20th-century avant-garde movements suggests a structured progression: realism leads to impressionism, which leads to cubism, and so on. This model assumes that new artistic movements render previous ones obsolete, but is this truly how art evolves?

Philosopher René Descartes contributed to this way of thinking by developing the Cartesian system—a structured, rational framework for understanding the world. This system relies on representation, where external objects are mapped onto an internal mental model. Magritte’s famous painting The Treachery of Images (featuring the words „This is not a pipe“ beneath a painted pipe) plays with this idea, exposing the gap between representation and reality. Language, images, and perception form a complex web of relationships that we may never fully understand.

This brings me to the concept of writing and its impact on human consciousness. Plato’s Phaedrus contains a story about the Egyptian god Thoth, who presented the invention of writing to King Thamus. The king rejected it, fearing that writing would weaken memory and disrupt the direct transmission of knowledge. This prediction was remarkably prophetic. Writing enables record-keeping and challenges authority, but it also shifts us from a world of direct experience to a world of textual knowledge. In oral traditions, knowledge is preserved through memory, sound, and direct teaching rather than through written records. Even today, Vedic traditions in India rely on extensive memorization, preserving knowledge in a way that differs fundamentally from text-based learning.

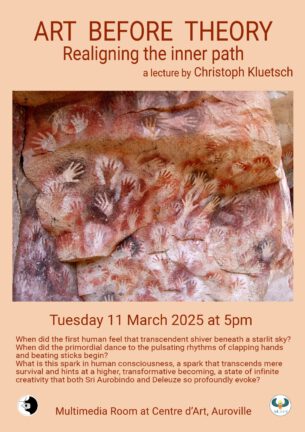

In contrast to textual knowledge, prehistoric art represents a more direct and unmediated form of expression. The handprints found in ancient caves around the world, created by blowing ochre pigment over hands pressed against rock walls, are an early form of artistic expression. These images appear in various cultures across millennia, suggesting a universal human impulse. Their purpose remains speculative—perhaps they served as a mark of presence, a spiritual act, or an attempt to connect with the environment in a personal way.

Similarly, early figurines such as the Venus of Willendorf and the Lion Man of Hohlenstein-Stadel suggest complex symbolic thought. The Venus figurine, with exaggerated reproductive features, likely represents fertility and life-giving power. The Lion Man, a humanoid figure with an animal head, implies an early exploration of hybrid identities, myth, and imagination. These artifacts demonstrate that early humans were not merely copying reality but engaging with deep existential questions.

Music also played a significant role in prehistoric culture. A 40,000-year-old pentatonic flute found in Germany suggests that early humans understood musical harmony. The pentatonic scale appears in various cultures and is present in the mathematical ratios of planetary orbits, indicating a deep, perhaps even intuitive, connection between music and the cosmos.

Art, music, and spiritual experience in prehistoric times were not separate disciplines but integrated aspects of human existence. Early cave paintings, sculptures, and musical instruments were not simply tools for survival or representation but ways of engaging with the world on a profound level. They allowed humans to connect with nature, with each other, and with something beyond the material world.

In the modern era, art has become increasingly intellectualized, often reduced to conceptual games and textual discourse. Yet, at its core, art originates from an urge to connect—to align our inner experience with the outer world. This is what I mean by „art before theory.“ Prehistoric art embodies a direct, unmediated encounter with existence. It speaks to something fundamental in us, something we may have lost in the distractions of contemporary life.

Perhaps the real challenge is to rediscover this connection—to step outside the text, outside the structures of theoretical discourse, and into a more immediate engagement with being. The question remains: how do we move beyond the text while still embracing the knowledge it provides? This is something I continue to explore in my own practice and in my engagement with art history.

Art before Theory