Auro Art World organized a series of 6 lectures at the Centre d’Art multimedia room in Auroville. These lectures, conducted by Dr. Christoph Kluetsch, explore connections between art, philosophy, and spirituality, bridging Eastern and Western traditions to illuminate the enduring questions of existence, consciousness, and creativity. The series is offered on the first Tuesday of every month.

Fourth lecture – Tuesday 7th January 2025 at 5pm

Who in our consciousness experiences sensations? How are sensations synthesized? How do matter, vibration, consciousness, and self connect? And how can we share sensations through art? Sri Aurobindo introduced the uncommon notion of intermiscence at a central point in his interpretation of the Kena Upanishad. This concept invites deeper speculation about the power of art and provides a profound tool to understand postmodern theories like Gilles Deleuze’s provocative reinterpretation of the notions of concept, percept, and affect. The Logic of Sensation (Deleuze) is an analysis of the forces in modern painting as an encounter. It will become clear that Aurobindo’s interpretation of the Kena Upanishad as a key text of the Vedanta can hold space for one of the most profound rhizomatic postmodern thinkers.

On a deeper level, we want to explore how Aurobindo’s idea that sensations can ‘operate without bodily organs’ relates to Deleuze’s notion of body without organs (BwO). Both philosophers point at the forces of consciousness on a plane of immanence.

Transcript:

I think I’m going to start slowly. Hello, welcome. Thank you for coming. I’ve been doing a lecture series here over the last couple of months. This is, I think, the fourth lecture I’m doing. They’re not really related; they’re all different topics. One was on temples, one on retinal art, one on apples and mangoes—just topics I find interesting.

It was an eye-opening experience when I discovered the Upanishads. I realized that not only are the Upanishads at least as deep as some of the most profound Western philosophies I’ve read, but they actually address a lot of questions I had been searching for. One of them was the question, “Who is seeing when seeing?” So I want to explore that a little bit. I will talk a bit about the Kena Upanishad. I’m not teaching it as a philosopher, because I don’t have the expertise to go too deeply into it, but I will use it as material. Then I want to contrast it with the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze, a French contemporary thinker who died in the 1990s—probably one of the most prolific postmodern thinkers of the 20th century.

The Laocoön, from around 27 AD, is probably one of the most famous sculptures. Winckelmann wrote about it, and the key phrase associated with it is “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur.” The way the bodies are intertwined—how Laocoön is fighting the serpent to protect his sons—really captures so much of the energy and essence that defines us as humans, expressing it in a beautiful way that engages the viewer.

So, when I look at the Kena Upanishad, I’ve highlighted a few things: “What gives sight to the eye and hearing to the ear?” I probably don’t need to explain much about this Upanishad to people here, but it makes us aware of how our senses work and what the binding force behind them is. It leads us to meditation and reflection on the relationship of Brahman and Atman. Sri Aurobindo wrote an extraordinary commentary on the Kena Upanishad, which I’ve read many times. It’s incredibly prolific, almost infinitely deep.

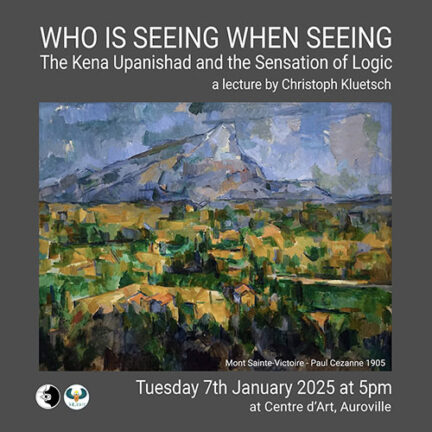

Looking at art in the 20th century, we can ask: What is art doing? What does it capture? One example is Vincent van Gogh, who painted shoes. Martin Heidegger wrote about those shoes, saying they capture the very essence of “shoeness.” He points out how we can see the earth under the soles, how they are worn. Another example is Paul Cézanne, who painted apples again and again—there’s something significant about painting an apple instead of simply eating it. Plato, in antiquity, famously mistrusted artists, calling them liars: if you paint an apple, you can’t eat it, so in a sense you’re deceiving people. But Cézanne might be indirectly responding to that by painting dozens of still lifes with apples, to show we can delve into our very own way of seeing and creating art, and reflect on the world.

When I was studying Sri Aurobindo’s commentary, I found a few ideas that really shook me awake. For instance, here is one of those insights: if we suppose that physical senses act through a physical body, we can explain physical phenomena that way. Still, that action is only an organization of the inherent functioning of the essential sense.

And I was reading this and thought, “Wow, this is Sri Aurobindo, talking about the Kena Upanishad, essentially discussing a ‘body without organs,’ which is usually associated with Gilles Deleuze’s way of thinking. And here it is!” I wondered what he meant—how one goes to the very essence of sensation and talks about it in a way that allows us to think about a body beyond our ordinary notion of organs.

It’s much less common to think of the body in that way. And Deleuze makes a proposal to consider the “body without organs” as something that brings thinking into art. He uses Francis Bacon as an example—a famous British painter known for distorted figures that convey pain and distress, expressing the suffering of the 20th century. But what Deleuze says is that when we look at a painting by Bacon, what we see is the actual sensation: not merely the face or how hair is flying around, but a subtler level—an inner working of the sensation someone in distress might have. It’s shown through what he calls the “logic of sensation.”

So, taking that term—“logic of sensation”—back into the Upanishads, what happens?

Sri Aurobindo, in his commentary on the Kena Upanishad, makes a distinction of five different elements. It’s quite a complex idea. I stumbled over the word “intermissence” because I didn’t know what it meant. When I looked it up, I saw maybe three books in the world use it. It’s a very obscure word, but a valid (though out-of-use) English term.

When Aurobindo discusses sensation in relation to the Kena Upanishad, of course he speaks about the five senses and the five elements, intertwining them. He starts by saying, first, we have rhythm, which is sound. Secondly, we have intermissence, this “flowing into each other,” which is touch. If I touch a surface, then my skin and the surface of the object are flowing into each other to a certain degree—otherwise, I wouldn’t be able to touch it. Something stops my body and makes clear there is something else there.

Third is shape, which relates to sight. Fourth is taste, involving “upflow,” or water. Fifth is the discharge or compression of force and movement, which he relates to smell—atoms evaporating from the object and being received by my nose. Beyond these correlations, there is something deeper, as Aurobindo notes. He’s exploring how these senses operate at a profound level.

So again, the correlation is:

- Rhythm = Sound

- Intermissence = Touch

- Shape = Sight

- Taste = Upflow/Water

- Compression/Discharge = Smell

I was thinking about what example of 20th-century art could help illustrate this. In 2009, I was at Tate Modern in London for the installation How It Is by Miroslaw Balka. In the Turbine Hall, there was this massive black container, completely dark inside. You walk in, and it’s really a journey into yourself. People move slowly. At the end, you turn around, and light pours in. You see everyone coming toward you, slowly, and you see how you yourself must have looked walking in. So there is this interplay between perception and self-awareness.

Sri Aurobindo, in his Kena Upanishad commentary, states that all the senses have a kind of complex unity. They aren’t separate compartments—hearing here, seeing there, taste there, all in isolated boxes within a human being. Instead, it’s a complex unity at the core.

So, in a way, seeing is connected to hearing, taste, and touch, and they all operate upon each other. I don’t want to go too deeply into modern scientific or philosophical discussions about “What if someone is blind or deaf?”—that might raise interesting questions, but at the core, it’s still valid that when we talk about consciousness, when I speak of my experience of the world, these senses flow together. A little like I said before: in Sri Aurobindo’s terms, there is rhythm, intermissence, form, the “upgoing force” (related to rasa), and compression of energy. Somehow, these aspects combine.

So, when we ask, “Who is seeing when seeing?” it’s really about the consciousness behind everything—whether you call it my consciousness, your consciousness, or Brahman in manifestation. There’s a larger consciousness of which we’re a part, and we participate in that manifestation, thereby allowing the world to “sense” itself.

Another example is James Turrell, a famous American light artist. His Roden Crater project has been in the works for decades; only recently have a few people seen it, and I, unfortunately, haven’t been there myself. He constructs these spaces that open up to the sky, blurring the boundaries between myself, the space I inhabit, and something deeper—the cosmos, the stars, silence. Some of his installations work on the very fine line of perceiving light in and of itself, dimmed down to such a degree that you just begin to see it. In that process, your mind passes through different levels of being—what some might call the chakras or the seven layers. In Indian thought, we might call them prana, rational mind, vijnana, philosophical view, sat-chit-ananda, and so on. The Upanishad guides us to become aware of these sensory and perceptual layers.

Images are fascinating when you think of them philosophically—not just as representations like a painting of something. Images are also what appear on our retina when we perceive. We have them in memory, in visions. I see you, you see me—we see each other. There is a way to think of images as the fundamental layer of our existence, because all I truly have of the world is my perception of it. I don’t directly have “the world” in my mind; I have a sensation of something, and that’s an image.

Henri Bergson is a philosopher who was very radical in this regard, and he’s one of the very few Western philosophers Sri Aurobindo acknowledged. Bergson essentially says that our consciousness is dealing with images only. Everything is an image—this object, that object, you, me. Even my body is a particular image, because consciousness has direct access only to these images. We don’t have direct access to “matter” in our consciousness. Modern science may talk about matter from an analytical perspective, but in our actual conscious experience, there is only this array of images.

These images also extend into our memory. I can tell you what I was doing yesterday; those memories consist of images. Yesterday no longer exists in the present world—it’s simply gone—but I have images of it. So, in a very strong phenomenological sense, it’s useful to pause and consider that all we have is this interplay of images, here and now.

We can make sense of images in many ways. We can contemplate them, compare them, act upon them, or even run away from them. There’s something very particular about the image of my body in relation to all the other images that can act on it. That is an extraordinary observation by Henri Bergson: if you follow the Upanishadic path inward to your own body, you’re essentially doing what Bergson describes—treating your body as an image. And the fact that we can act upon other images is found in meditation through the Upanishads, which always point to the force behind everything. Bergson, Deleuze, and others may discuss it differently, but the Upanishads call it Brahman or that deeper principle.

Mark Rothko gives a good example of this in his color-field paintings. One might say if you’ve seen one Rothko, you’ve seen them all—two or three rectangular color fields relating to each other. Yet if you visit a large Rothko retrospective, you see dozens of them, and it’s mind-blowing. The tension between the colors and the way they float over a background color create a field of sensation. In painterly terms, that field of sensation is close to what Gilles Deleuze refers to as the plane of immanence—the most fundamental layer. You might think of that layer as Brahman in the Advaita sense: “There is only one reality,” which unfolds into complexity. That complexity is necessary for anything to be set in motion. Once set in motion, experience becomes possible, and that is how existence gains a sense of itself.

Such unfolding can only happen through time, through duration, through actual movement. People often say Earth is where things “come down” to be worked out—whether you call it divine consciousness, soul, or something else. It must take concrete form in reality to experience itself and evolve. Visually, to me, that’s what Rothko’s fields suggest.

Now, going to the concept of the body without organs in the sense of immanence: consider this as an illustration—Deleuze doesn’t specifically talk about it this way, but it’s a helpful image. When Deleuze discusses the plane of immanence, he views it as having a transcendental field where action and becoming are possible—where “sense-creation” can happen. It’s not just the material world we walk around in, but a subtler level that allows a different way for things to emerge.

Deleuze often gives the example of an egg: at first, you have yolk and white, which seem like formless mass. Many of us eat this for breakfast without a second thought, but if you let it incubate, there’s already a chicken in there, in some virtual sense. That’s the “body without organs” concept: the egg already contains the chicken, even if it’s not yet realized.

By the same token, my body or your body is a body working with sensations, consciousness, and the analytical mind. We enter the world, connect with each other, speak, form communities, develop institutions, come up with knowledge systems, and create science and art. Through all this, we produce the complexity of modern societies. We reflect on reality in an analytical way, dissecting, reassembling, and building. We invent computers and projectors for gatherings like this. In doing so, we generate new intensities, new connections, new ways of being.

In interacting with these systems—institutions, electoral processes, laws—there emerges something that operates on its own. It can improve our lives or make them worse. But it functions as a body in itself, an agency in our reality that acts like a “body without organs.” That’s the power of Deleuze and Guattari: they analyze how society works (or doesn’t), describing problems as a sickness in that body. Recognizing the sickness is the first step to talking about a cure.

Deleuze and Guattari’s analysis of capitalism and schizophrenia basically uses this idea of seeing society as a body that’s not functioning properly—one that is “sick.” Once you recognize there’s something wrong in the complex system, you can talk about how to fix it. But first, you need to understand that it’s not simply about you or me making one or two changes.

Moving on to a more primary level with Deleuze, he talks about percepts, affects, and concepts. If we want to understand how these realities connect to our consciousness, we need to recognize these categories. A percept is not just my perception. When I look at this pen, there’s a perception of a pen, which means my consciousness is directed toward it, and at the same time, the pen “presents itself” to me. You, looking from another angle, see the other side of it. Deleuze calls that pre-personal “something” a percept—prior to our individual perception, and not simply the object itself.

Deleuze says these percepts are akin to what Bergson might call “images.” We could think of them as “inner senses.” If you go into the Upanishads, you can go much deeper into this. Essentially, percepts are something we can work with; the realm of art taps into that directly.

Similarly, affects are emotions—fear, joy, love, pain—which occur before I even become consciously aware of them. They’re triggered pre-subjectively in my nervous system. So Deleuze’s idea is that if we look at the complex interplay between the outside world and my inner being—between my sensations, how my consciousness is composed of images, percepts, and affects—we can then see how these can be reworked or rearranged. This leads to a “logic of sensation,” which is an awkward kind of move and not many philosophers do it. Deleuze is in many ways unique; you could even call him a kind of “Advaita philosopher,” although he would describe it as “materialist immanence.” He’s non-committal about whether it’s consciousness or matter, saying it’s just one plane on which things happen.

Paul Cézanne exemplifies this fragmentation of our perception perfectly. He painted Mont Sainte-Victoire about seventy times, breaking the scene into brushstrokes. None of those individual strokes represents anything by itself. Only together do they form what looks like a field, a mountain, trees, houses. But it’s not photographic realism. We have to think: How am I assembling these strokes to see the landscape? It’s almost a meditative process—a deeply spiritual encounter with reality.

Shifting back to Francis Bacon: if we consider percepts, affects, sensations, and distortion, and we look at one of his triptychs, we immediately see a formal, rhythmic structure of three images. It’s reminiscent of a traditional Western altarpiece. We might see the same entity repeated, but the body depicted is utterly different from a normal human body—it’s reduced or distorted. It seems alive, though not in a straightforward, representational way. I can feel the motion, sense it, and sympathize with the affects it conveys. We see a pre-subjective consciousness of affect rendered visually in these percepts.

Deleuze sometimes draws diagrams to illustrate this. He talks about geological strata—how the Earth has molten magma inside, with layers of stone forming the crust, and tectonic plates shifting to create mountains. Through this folding process, insides and outsides form. Once there is a fold, it can vibrate, leading to dialogue, rhythm, and refrain.

Inside the Earth, you have magma. As the planet cools and solidifies, different layers of stone form. Then there are tectonic movements—continents moving toward or away from each other—creating mountains and folds. Eventually, things fold, and when they fold, you get an inside and an outside; there’s some sense of identity forming within that fold.

Once you have that, things can vibrate, get into a dialogue, or find a rhythm. For instance, if I knock on a surface, and then you knock in response, those two knocks can start a drum session—there’s a shared rhythm. That rhythm creates something, perhaps a territory, an area in which we find ourselves. Often, drum rhythms are used to signal to others that people are present—for invitation, to scare, to attack, or to celebrate. In any case, it defines a territory, and within that territory, social events happen.

This connects to a part of Deleuze’s philosophy of art that states art is ultimately an intersection of different planes of knowledge. He describes a plane of immanence, a plane of concepts, and yet another plane. Think of it in terms of wide conceptual planes for thinking about the world. If you intersect them on a very abstract level, you create an inside and an outside—like building a house, in a metaphorical sense. You surround yourself with art, books, ideas, people; you have a belief system and a way of anchoring yourself in reality; you relate to nature in a specific way, eat certain things, care about certain things.

That’s how the plane of immanence unfolds in Deleuzian terms. In Upanishadic terms, it might be Brahman bringing itself into existence. It’s not an exhaustive interpretation, but it’s one way of describing it.

To illustrate this, consider a flock of birds, like the seven sisters or myna birds. There’s a rhythm to how they fly around and chatter. They create a territory and invite others in. Sometimes a different bird joins them—sometimes not. They move on, rearrange, and so forth.

Coming toward the end, let’s revisit the Kena Upanishad. It doesn’t actually start with seeing; it starts with speech: “By whom impelled does this word [speech] arise?” In other words, who is speaking when I am speaking? It’s not really “me.” We know this idea from the motif of Shiva’s drum, from which syllables and language come—the beginning of the word itself.

Sri Aurobindo, in his commentary on the Kena Upanishad, writes:

“Brahman expresses by the word a form of presentation of himself in the objects of sense and consciousness, which constitutes the universe, just as the human word expresses a mental image of those objects.”

Here, Brahman focuses on objects through the word, and humans also focus on objects through the word—but obviously they do so in very different ways. Brahman is expressing through sense and consciousness, constituting the universe.

In looking for a Western counterpart, I remembered Eduardo Kac, a South American media artist, and his experimental project called Genesis. He works with E. coli bacteria, splicing in new genetic code—DNA art, in a sense. It’s a controversial territory in its own right, but it reflects these questions of creation, expression, and what it means to bring something into being through a “word” or a code.

Eduardo Kac took a sentence from the Bible’s Genesis—“Let man have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth”—so when we speak of Genesis, “In the beginning was the word,” and at the end of Genesis there’s this notion of man’s power to dominate the earth. That’s a very different understanding of how words can be used. Sri Aurobindo often talks about words as the most powerful means to manifest, to bring something into existence. In spiritual practice, you use words and mantras to transform yourself; the vibration and the sound of words create reality. Brahman forms the world through words.

What I’ve tried to do here is intersect these profound observations from the Kena Upanishad and Sri Aurobindo’s extraordinary interpretation, looking at “Who is sensing when sensing?” and connecting it with postmodern thinking. Both inform each other quite well. It helps me understand what art is ultimately about on a very deep level—art can be transformative. I’m sure most of us have experienced looking at an artwork for hours, not knowing why, but feeling that it did something to us. Our mind goes into that artwork, entering its plane of sensation, that logic of sensation, beyond narrative—beyond, “Oh, this is the artist, that’s the subject, here’s the story.” It’s more about really seeing. “Who is seeing when seeing?” is the question. When you engage with an artwork, when you really try to see and observe, that’s where transformation can happen.

Any comments or questions about the “body without organs”? It’s a concept most famously associated with Gilles Deleuze, the French postmodern philosopher. He borrowed it from Antonin Artaud, who was known in the early 20th century as an actor and theatrical theorist. Artaud wrote about the “theater of cruelty.” It was a way of creating a shock, exposing the body to forces that propel us into being affected. Film itself is another way of dealing with percepts that evolve under distress, as in “theater of cruelty.” One connects to these forces—there’s torture or conflict in a certain place—and it all extends into that early idea of the “body without organs.”

Somehow, it all echoes in Sri Aurobindo’s analysis of the Kena Upanishad. Don’t ask me why—I just found it striking. Deleuze came decades later, and I’m sure Sri Aurobindo wasn’t thinking about the theater of cruelty. But there’s an eerie overlap.

DISCUSSION:

Audience:

Then there’s this other point in the Upanishads about “seeing” or “vision.” In English, we say, “I see what you mean.” William Blake famously said, “To see a world in a grain of sand, and a heaven in a wild flower.” How do you see the world in a grain of sand? He’s not talking about looking through a microscope; he’s talking about a different set of eyes. And you have Meister Eckhart in the 13th century saying, paraphrased, “The eye with which I see God is the eye with which God sees me.” That’s an entirely different kind of relationship.

Yes, exactly.

One more mention: the artist who used brushstrokes to indicate a mountain was Paul Cézanne. You said he painted it 70 times in a meditative process?

Yes, he painted the same mountain—Mont Sainte-Victoire—70 times, possibly from different angles. He lived close to it, would walk around, choose different viewpoints, but essentially kept to the same subject. Over that series, he became more and more abstract. He’s considered the father of Cubism—Picasso was heavily influenced by him—one of those breakthrough artists like Kandinsky, only earlier.

Audience Member:

And the artist who makes these deformed images—sometimes it’s unpleasant to look at. It provokes something that isn’t a happy feeling. It’s like the “theater of cruelty.” I understand that was the aim: to create that kind of reaction. These works were painted for museums. They could be marketed. In the past century, a lot of modern art leans in that direction: beauty in the traditional sense is often abandoned. There is still a market for it, but it focuses on creating a shock or disturbance. It reflects what the artist sees inside himself.

I watched a documentary about one such artist; his studio was a mess. He was clearly disturbed, but we still place him very high in the art world, even calling him a genius. Over time, I’ve started to change my taste. One of my favorite artists was Burri—I’m sure you know him, Alberto Burri, the Italian. One of his works was… well, it depicts great pain. It reflects what the world is going through right now. That pain is put onto the canvas.

Of course, people can go watch a Disney movie if they want an escape from the world. This kind of art, however, represents a harsh reality. It provokes a reaction. Maybe it helps us confront the fact that the world is in pain, and it inspires us to change it. After the Enlightenment in the West, the notion arose that spirituality, religion, or any non-scientific thinking should be set aside—that was part of the Enlightenment process. But it’s an interesting twist on the word “enlightenment,” almost the opposite of what we might mean in a spiritual sense.

Lecturer (responding):

Yes, I think that after the Enlightenment, art did jump on that train: it dove into the ugly, the painful, the disturbing, the unusual, the provocative—anything the rational mind can examine and say, “This is pain, this is perception.” And from a modern perspective, originality often became the main criterion: you just have to do something new, whether it’s admirable or not. That’s the logic many follow, though personally, I don’t think that logic applies here.

Audience Member:

What’s your point of view on art, then? What’s your definition or meaning of art?

Lecturer:

I’ve had to redefine my view. Part of why I’m doing these lectures is that I’m partly saying goodbye to some of those assumptions. I’ve been disturbed by this for a decade. Sure, I was initially excited by artists like Francis Bacon, seeing all that pain. But at a certain point, I realized that if I look at Bacon through Deleuze and through the Kena Upanishad and Sri Aurobindo, I find something deeper that I want to keep. I don’t care about the treadmill of modernity anymore.

It’s a personal and sometimes painful process. We also have to recognize that we’re unconsciously addicted to certain emotions—sometimes even unpleasant ones. We seek experiences or images, including art, that feed those emotions. So these paintings can be a way people indulge in that.

Another Audience Member:

Regarding astrology and planets: In Sanskrit, the word for “planet” is “graha,” meaning “to grasp.” The planets themselves do nothing, but they “grasp” your mind and direct your perception or actions, engineering certain experiences for you. From another perspective, in the body, Saturn rules the nervous system, and the nervous system is the foundation of whatever experience you have. The Sun rules the bones, etc. In that sense, you see parallels to the concept of “affect” that we discussed—something preexistent to humans.

Another Audience Member:

From a Western viewpoint, that might be new, but from an Eastern viewpoint, it’s familiar. And about the Enlightenment you mentioned: I recently read about a meeting of all the world’s religions, including the Dalai Lama and various Christian representatives, and one priest pointed out that the Enlightenment was, in a way, a scientific “proving” of certain constitutions, but we got confused and thought it meant discarding religion altogether. It’s a tragic misunderstanding.

Lecturer (concluding):

Yes, indeed—it’s a very tragic confusion. Alright, thank you all for coming!